Should Western firms remain operating in or selling to Russia? Can Greek shipping companies continue to transport Russian oil with good conscience after the EU’s decision on an oil embargo? Should Siemens have moral concerns about selling high-speed trains to Egypt? How to deal with the reports around the Xinjiang police files; would Novartis have to close its pharmaceutical office in Urumqi? Is it morally acceptable for tourism companies such as booking.com to continue offering hotels in Myanmar after the 2021 coup d’état?

As soon as firms engage in international business things quickly get morally less clear compared to a completely domestic business model. Often this relates to corruption, but also other questions will appear on the radar screen: How many vacation days should a Danish company (minimum of 25 paid vacation days) offer to local employees when opening an office in Thailand (minimum of 6 paid vacation days)? Can a French automotive company continue to offer Wine at supplier events? Will you send a gay or female sales representative to Saudi Arabia?

Most companies quickly develop coping strategies to balance different moral values and priorities across their different locations. But as soon as fundamental questions around live and death (war!) or human rights are involved, most people intuitively hesitate to just recommend the good old: “when in Rome do as the Romans do.” What to do in such cases? When might it be morally necessary to discontinue international business?

In such situations, two key phases need to be differentiated:

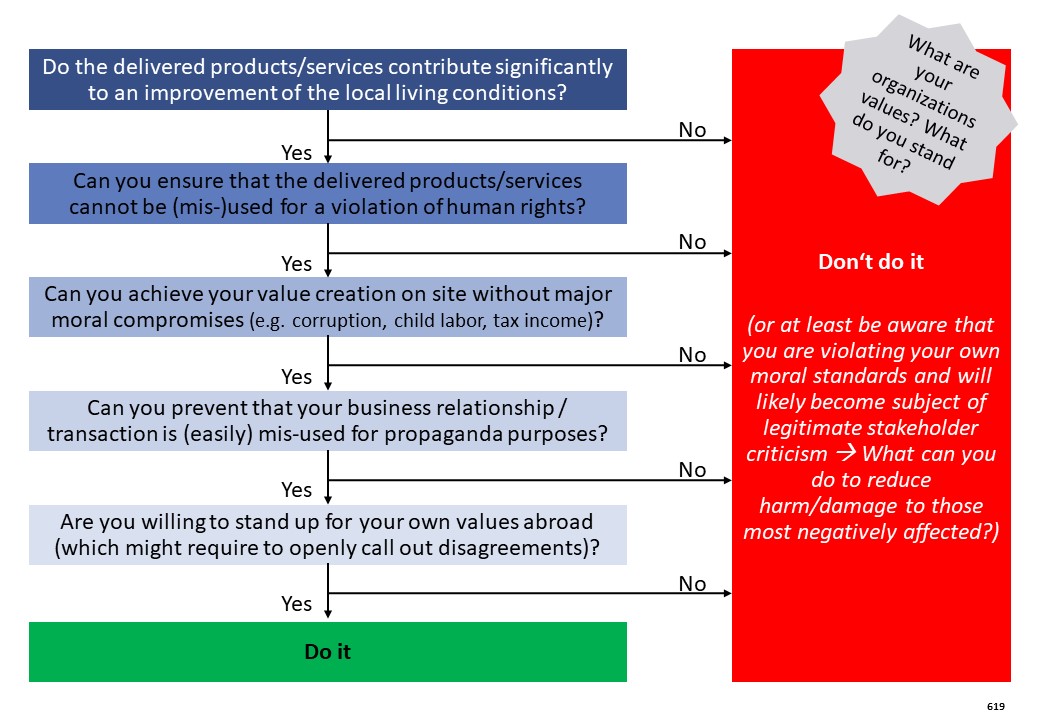

Phase 1 Decision: Is it morally acceptable for you to continue doing business with/in a country with which you disagree morally about fundamental values such as human rights?

To take the decision about dis-/continuation, managers should ask and answer five key questions:

- Do the delivered products/services contribute significantly to an improvement of the local living conditions? (Example: Do you sell snacks or essential pharmaceutical products?)

- Can you ensure that the delivered products/services cannot be (mis-)used for a violation of human rights? (Example: Can your machinery be misused to produce chemical weapons?)

- Can you achieve your value creation on site without major moral compromises? (Example: Would you need to engage in major corruption?)

- Can you prevent that your business relationship/transaction is (easily) mis-used for propaganda purposes? (Example: Would you have to take a picture with a dictator to close the deal?)

- Are you willing to stand up for your own values abroad (which might require to openly call out disagreements)?

If the answer to one of these questions is “no” you would either have to discontinue your operation or at least be very clear to yourself and your key stakeholders that you are violating your own moral standards. So better be ready to face legitimate stakeholder criticism and constantly ask yourself if there is anything you can do to reduce harm to those most negatively affected.

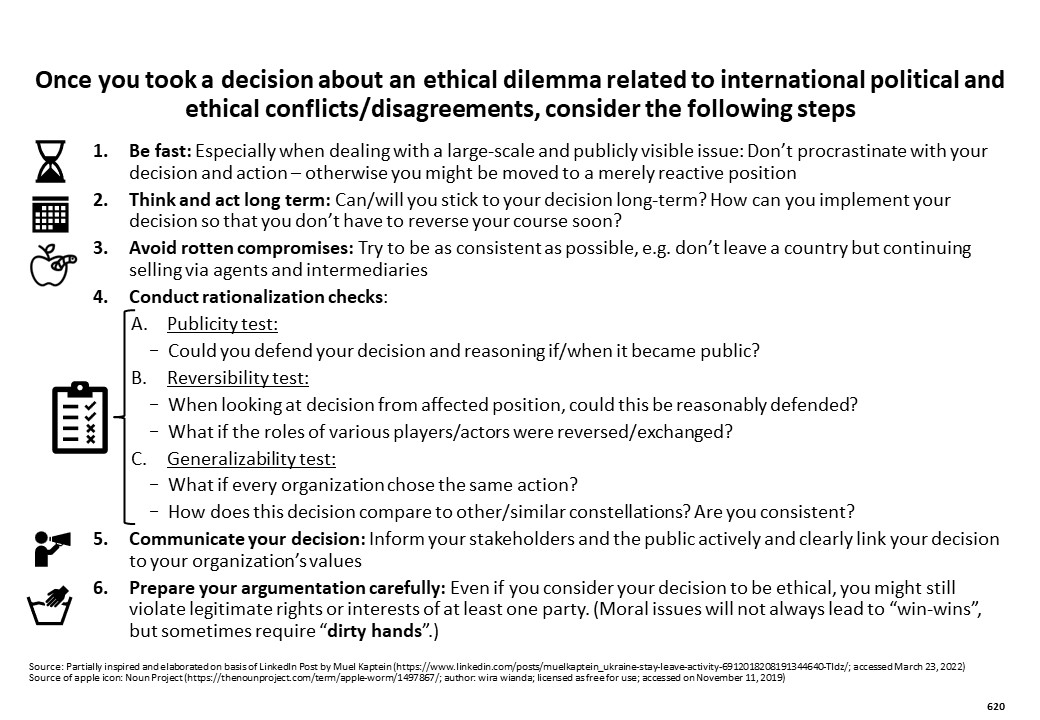

Phase 2 Execution: Once you have taken the decision about dis-/continuing on basis of the five questions above: How should you implement your decision? Here are six recommendations for the implementation:

- Be fast: Especially when dealing with a large-scale and publicly visible issue: Don’t procrastinate with your action – otherwise you might be moved to a merely reactive position and lose credibility with your stakeholders.

- Think long-term: Can/will you stick to your decision in the long run? How can you implement your decision so that you don’t have to reverse your course soon?

- Avoid rotten compromises: Try to be as consistent as possible, e.g. don’t leave a country officially just to continue selling through agents and intermediaries.

- Conduct rationalization checks: Avoid using moral reasoning that is self-serving, by challenging your argumentation through these three tests:

- Publicity test:

- Could you defend your decision and reasoning if/when it became public?

- Reversibility test:

- When looking at your decision from the affected position, could this be reasonably defended?

- What if the roles of various players/actors were reversed/exchanged?

- Generalizability test:

- What if every organization chose the same action?

- How does this decision compare to other/similar constellations? Are you consistent?

- Publicity test:

- Communicate your decision: Inform your stakeholders and the public actively and clearly link your decision to your organization’s values

- Prepare your argumentation carefully: Even if you consider your decision to be ethical, you might still violate legitimate rights or interests of at least one party. (Moral issues will not always lead to win-win constellations.)

When working your way through these questions you will probably realize that the morally right decision is not necessarily always a discontinuation even if the public might be calling you to do so forcefully. Sometimes you might be ethically allowed or even required to continue doing business even with countries in war or with horrible human rights records, e.g. if you provide life essentials (e.g. food, pharmaceuticals, electricity etc.) and can do so in a reasonably clean way. But in many other constellations you will realize that you might need to bite the bullet and shut down parts of your business for moral considerations.